Lyndon B. Johnson: Domestic Affairs

The Lyndon Johnson presidency marked a vast expansion in the role of the national government in domestic affairs. Johnson laid out his vision of that role in a commencement speech at the University of Michigan on May 22, 1964. He called on the nation to move not only toward "the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society," which he defined as one that would "end poverty and racial injustice." To that end, the national government would have to set policies, establish "floors" of minimum commitments for state governments to meet, and provide additional funding to meet these goals. By winning the election of 1964 in a historic landslide victory, LBJ proved to America that he had not merely inherited the White House but that he had earned it. The election's mandate provided the justification for Johnson's extensive plans to remake America. Large Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, along with Johnson's ability to deal with powerful, conservative southern committee leaders, created a promising legislative environment for the new chief executive.

The Great Society

Johnson labeled his ambitious domestic agenda "The Great Society." The most dramatic parts of his program concerned bringing aid to underprivileged Americans, regulating natural resources, and protecting American consumers. There were environmental protection laws, landmark land conservation measures, the profoundly influential Immigration Act, bills establishing a National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Highway Safety Act, the Public Broadcasting Act, and a bill to provide consumers with some protection against shoddy goods and dangerous products.

To address issues of inequality in education, vast amounts of money were poured into colleges to fund certain students and projects and into federal aid for elementary and secondary education, especially to provide remedial services for poorer districts, a program that no President had been able to pass because of the disputes over aid to parochial schools. Johnson, a Protestant, managed to forge a compromise that did provide some federal funds to Catholic parochial schools. He signed the bill at the one-room schoolhouse that he had attended as a child near Stonewall, Texas. With him was Mrs. Kate Deadrich Loney, the teacher of the school in whose lap Johnson sat as a four-year-old.

To deal with escalating problems in urban areas, Johnson won passage of a bill establishing a Department of Housing and Urban Development and appointed Robert Weaver, the first African American in the cabinet, to head it. The department would coordinate vastly expanded slum clearance, public housing programs, and economic redevelopment within inner cities. LBJ also pushed through a "highway beautification" act in which Lady Bird had taken an interest. For the elderly, Johnson won passage of Medicare, a program providing federal funding of many health care expenses for senior citizens. The "medically indigent" of any age who could not afford access to health care would be covered under a related "Medicaid" program funded in part by the national government and run by states under their welfare programs.

The War on Poverty

LBJ's call on the nation to wage a war on poverty arose from the ongoing concern that America had not done enough to provide socioeconomic opportunities for the underclass. Statistics revealed that although the proportion of the population below the "poverty line" had dropped from 33 to 23 percent between 1947 and 1956, this rate of decline had not continued; between 1956 and 1962, it had dropped only another 2 percent. Additionally, during the Kennedy years, the actual number of families in poverty had risen. Most ominous of all, the number of children on welfare, which had increased from 1.6 million in 1950 to 2.4 million in 1960, was still going up. Part of the problem involved racial disparities: the unemployment rate among black youth approached 25 percent—less at that time than the rate for white youths—though it had been only 8 percent twenty years before.

To remedy this situation, President Kennedy commissioned a domestic program to alleviate the struggles of the poor. Assuming the presidency when Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson decided to continue the effort after he returned from the tragedy in Dallas. One of the most controversial parts of Johnson's domestic program involved this War on Poverty.

Within six months, the Johnson task forces had come up with plans for a "community action program" that would establish an agency—known as a "community action agency" or CAA—in each city and county to coordinate all federal and state programs designed to help the poor. Each CAA was required to have "maximum feasible participation" from residents of the communities being served. The CAAs in turn would supervise agencies providing social services, mental health services, health services, employment services, and so on. In 1964, Congress passed the Economic Opportunity Act, establishing the Office of Economic Opportunity to run this program. Republicans voted in opposition, claiming that the measure would create an administrative nightmare, and that Democrats had not been willing to compromise with them. Thus the War on Poverty began on a sour, partisan note.

Soon, some of the local CAAs established under the law became embroiled in controversy. Local community activists wanted to control the agencies and fought against established city and county politicians intent on dominating the boards. Since both groups were important constituencies in the Democratic Party, the "war" over the War on Poverty threatened party stability. President Johnson ordered Vice President Hubert Humphrey to mediate between community groups and "city halls," but the damage was already done. Democrats were sharply divided, with liberals calling for a greater financial commitment—Johnson was spending about $1 billion annually—and conservatives calling for more control by established politicians. Meanwhile, Republicans were charging that local CAAs were run by "poverty hustlers" more intent on lining their own pockets than on alleviating the conditions of the poor.

By 1967, Congress had given local governments the option to take over the CAAs, which significantly discouraged tendencies toward radicalism within the Community Action Program. By the end of the Johnson presidency, more than 1,000 CAAs were in operation, and the number remained relatively constant into the twenty-first century, although their funding and administrative structures were dramatically altered—they largely became limited vehicles for social service delivery. Nevertheless, other War on Poverty initiatives have fared better. These include the Head Start program of early education for poor children; the Legal Services Corporation, providing legal aid to poor families; and various health care programs run out of neighborhood clinics and hospitals.

Overall government funding devoted to the poor increased greatly. Between 1965 and 1968, expenditures targeted at the poor doubled, from $6 billion to $12 billion, and then doubled again to $24.5 billion by 1974. The billions of dollars spent to aid the poor did have effective results, especially in job training and job placement programs. Partly as a result of these initiatives—and also due to a booming economy—the rate of poverty in America declined significantly during the Johnson years. Millions of Americans raised themselves above the "poverty line," and the percentage under it declined from 20 to 12 percent between 1964 and 1974. Nevertheless, the controversy surrounding the War on Poverty hurt the Democrats, contributing to their defeat in 1968 and engendering deep antagonism from racial, fiscal, and cultural conservatives.

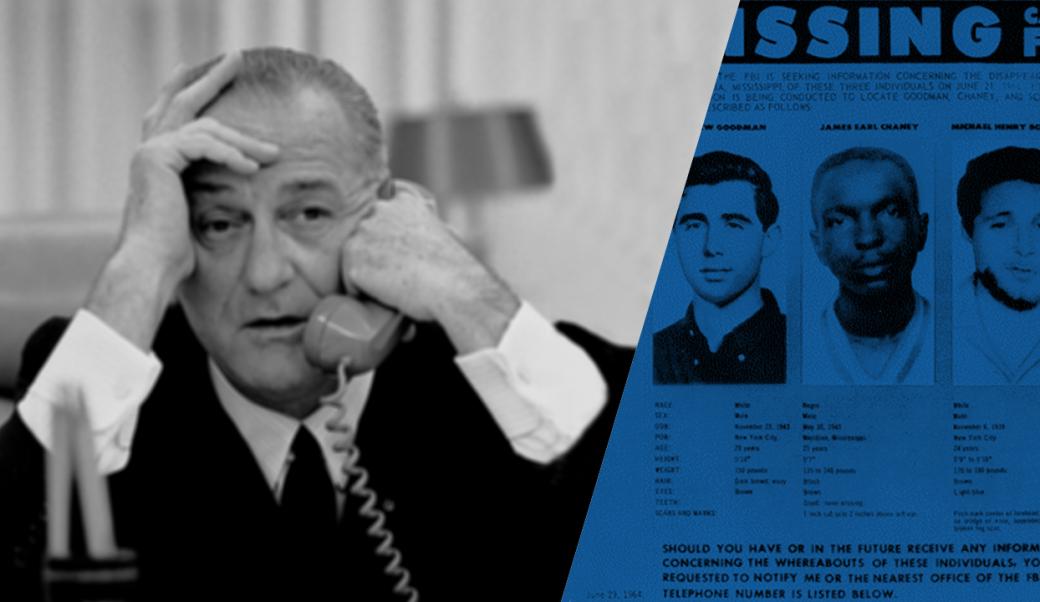

Civil Rights and Race Relations

Johnson was from the South and had grown up under the system of "Jim Crow" in which whites and blacks were segregated in all public facilities: schools, hotels and restaurants, parks and swimming pools, hospitals, and so on. Yet even as a senator, he had become a moderate on race issues and was part of efforts to guarantee civil rights to African Americans. When Johnson assumed the presidency, he was heir to the commitment of the Kennedy administration to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ending segregation in public facilities. As a result of his personal leadership and lobbying with key senators, he forged a bipartisan coalition of northern and border-state Democrats and moderate Republicans. These senators offset a coalition of southern Democrats and right-wing Republicans, and a bill was passed. It made segregation by race illegal in public accommodations involved in interstate commerce—in practice this would cover all but the most local neighborhood establishments.

The following year, civil rights activists turned to another issue: the denial of voting rights in the South. Since the 1890s, blacks had been denied access to voting booths by state laws that were administered in a racially discriminatory manner by local voting registrars. These included (1) literacy tests which could be manipulated so that literate blacks would fail; (2) "good character" tests which required existing voters to vouch for new registrants and which meant, in practice, that no white would ever vouch for a black applicant; and (3) the "poll tax" which discriminated against poor people of any race. The poll tax was eliminated by constitutional amendment, which left the literacy test as the major barrier. In 1965, black demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, marching for voting rights were attacked by police dogs and beaten bloody in scenes that appeared on national television.

In response to public revulsion, Johnson seized the opportunity to propose the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This piece of legislation provided for a suspension of literacy tests in counties where voting rates were below a certain threshold, which in practice covered most of the South. It also provided for federal registrars and marshals to enroll African American voters. The law was passed by Congress, and the results were immediate and significant. Black voter turnout tripled within four years, coming very close to white turnouts throughout the South. Blacks entered the previously "lily white" Democratic Party, forging a biracial coalition with white moderates. Meanwhile, white conservatives tended to leave the Democratic Party, due to their opposition to Johnson's civil rights legislation and liberal programs. Many of these former Democrats joined the Republican Party that had been revitalized by Goldwater's campaign of 1964. The result was the development of a vibrant two-party system in southern states—something that had not existed since the 1850s.

Even with these measures, racial tensions increased. In addition, the civil rights measures championed by the President were seen as insufficient to minority Americans; to the majority, meanwhile, they posed a threat. Between 1964 and 1968, race riots shattered many American cities, with federal troops deployed in the Watts Riots in Los Angeles as well as in the Detroit and Washington, D.C., riots. In Memphis in the summer of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., one of the leaders of the civil rights movement, was gunned down by a lone assassin. There were new civil disturbances in many cities, but some immediate good came from this tragedy: A bill outlawing racial discrimination in housing had been languishing in Congress, and King's murder renewed momentum for the measure. With Johnson determined to see it pass, Congress bowed to his will. The resulting law began to open up the suburbs to minority residents, though it would be several decades before segregated housing patterns would be noticeably dented.

Although the Great Society, the War on Poverty, and civil rights legislation all would have a measurable and appreciable benefit for the poor and for minorities, it is ironic that during the Johnson years civil disturbances seemed to be the main legacy of domestic affairs. Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to inquire into the causes of this unrest, and the commission reported back that America had rapidly divided into two societies, "separate and unequal." It blamed inequality and racism for the riots that had swept American cities. Johnson rejected the findings of the commission and thought that they were too radical. By 1968, with his attention focused on foreign affairs, the President's efforts to fashion a Great Society had come to an end.